Five abandoned towns that were formerly located inside the boundaries of Banff National Park provide a glimpse into the past of Banff’s frontier. In this article, I’ll outline the intriguing background of these ghost towns as well as their original locations.

While Banff is known for its stunning nature and abundant wildlife, few know the park used to have five towns within its borders besides Banff and Lake Louise.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, you could find Siding 29, Bankhead, Silver City, Anthracite, and Minnewanka Landing within the park’s current-day perimeter.

The story of the latter town is particularly fascinating. These days it’s like the Atlantis of the Rockies, submerged in Lake Minnewanka. If you’re into diving, you can still visit its old buildings and infrastructure.

Anthracite was built 6.5 kilometers (4 mi) northeast of the town of Banff at the foot of Cascade Mountain. It was a coal mining community.

Siding 29 was named after the railroad’s 29th siding from Medicine Hat in eastern Alberta, near the waterfall of Cascade Mountain. It later became the town of Banff.

Bankhead was close to Minnewanka Landing. You can still find some remnants of this former mining town.

Silver City was a raucous prospector’s town at the base of Castle Mountain that lured many fortune hunters to the area during the Canadian Pacific railroad construction.

Siding 29

![Canadian Pacific Railway log station, Banff National Park, Alberta, [ca. 1890-1891], (CU1115051) by Boorne and May](https://parkpilgrim.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/siding-29-railway-station-banff-1024x770.jpg)

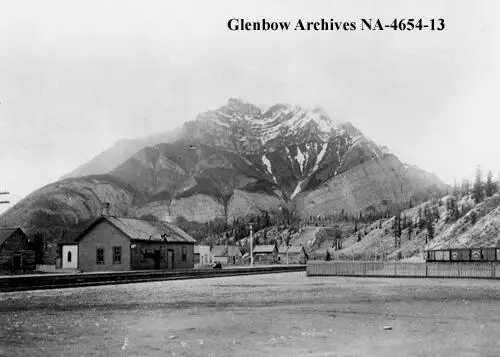

With the railroad construction through the Rockies, Siding 29 was developed near Cascade Mountain, just north of the current-day town of Banff. The siding itself was laid on October 27, 1883.

Two years earlier, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had arrived in the area. It was on its mission to build a railroad through the Rocky Mountains, heading west. The route was determined using information from Canadian government reconnaissance teams. These had been visiting the area since the 1880s to map possible routes.

Soon after the construction of Siding 29, the site’s development started northeast of the current-day Compound Road and Hawk intersection. Log buildings were erected north and south of the tracks, including a lumber yard, a general store, a butcher shop, a furniture shop, and a billiard saloon. A hotel, the Alpine Motel, emerged as well.

![General store of A. Ferland and Company, Banff, Alberta, [ca. 1880s], (CU187397) by Bingham, F. V.. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary](https://parkpilgrim.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/general-store-siding-29-banff-1024x602.jpg)

On November 25, 1883, not even a month after Siding 29 was built, co-founder of the CPR Lord Strathcona changed the town’s name to Banff, after the Scottish birthplace of Strathcona’s cousin and CPR president George Stephen.

After the Banff Springs Hotel opened on June 1, 1888, the CPR decided to build a new train station southwest of Siding 29 near the new settlement under the name of Banff. This gave the Siding 29 location the unofficial name “Old Banff”.

Some people who lived there moved their homes to the new town site. In 1897 Siding 29 was no longer there.

Minnewanka Landing

In 1885 Rocky Mountain Park, as Banff National Park was called in those days, opened to tourists. In addition to the town of Banff, the neighboring Minnewanka Landing was created, intended as a summer resort.

In 1895, a small wooden dam was built at the lake’s outlet across Devil’s Creek to regulate the water level at the wharf.

The government laid lots for villas, and in 1886 and 1887, Willoughby John Astley and W. H. Desbrowne built the Beach House Hotel, which soon became popular with city dwellers from Calgary. Most of them were people of stature, such as doctors and politicians. Later, tourists from abroad also stayed there.

The small community on the lake of the same name had four avenues and three streets with hotels, wharves and restaurants. There were even sailing trips. In those days, Minnewanka Landing had indeed become a summer resort town.

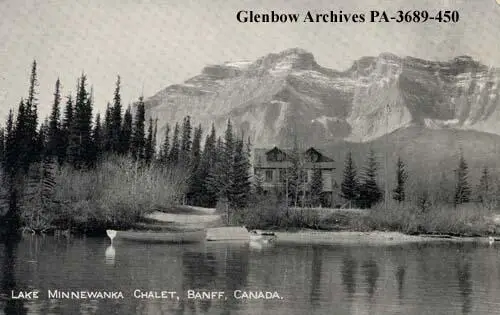

In 1899 CPR, which recognized Minnewanka Landing’s potential, built a 61 meters (200 ft) long pier in the lake. A few years later, Norman Luxton built a chalet on the south shore. He operated a cruise ship as well.

Meanwhile, the dam built in 1895 had proven ineffective. In 1912, the federal government granted Calgary Power permission to construct another, bigger dam on the lake. It regulated the flow to the Bow River and the Seebe power stations. Astley’s successor, the Reverend Basil Guy Way, who had run the hotel since 1903, was forced to burn the Beach House Hotel to the ground because of what was coming.

Chalet at Lake Minnewanka. It was removed in the summer of 1912, [ca. 1890-1909] (CU1156046).

Luxton did the same. When the dam was being built, he set fire to his cabin and started building a new one on the north shore. The same fate struck him yet again. During the construction of the second dam, he sold his business and cruise ship.

The dam caused the water level to rise by 3.7 meters (12 ft), and it inundated an area of more than 4,000 m2 (.098 acre), including the location of the former Beach House Hotel. Part of Minnewanka Landing had disappeared underwater, but in the following two decades, dozens of new houses were built on higher ground between Cascade Bay and the main lake.

In 1940, the construction of the third dam began downstream of the old one at the end of Devil’s Canyon. It was completed in 1941. The construction was possible thanks to the War Measures Act. It overruled the National Park Act, which excluded industrial development within the boundaries of national parks.

During the third dam’s construction, all Minnewanka Landing residents were forced to leave their homes. When the construction was completed, the water rose as much as 30 meters (98 ft). This time the water swallowed the entire village, including the second dam, and the lake was nearly doubled in size.

Lake Minnewanka has had an underwater ghost town ever since. Not surprisingly, the lake is popular with divers. Every year some 8,000 adventurers dive into the hidden remains of Minnewanka Landing.

Anthracite

As the CPR pushed through the Canadian Rockies, prospectors, traders, and other businessmen started to explore the Bow Valley.

Timber permits were taken out first. But in 1883, coal was found at Anthracite, the last station before Siding 29 for trains coming from the east. Initially, it was mined for personal use, but in 1885, the Anthracite Coal Company took over.

People looking for work and a better life flocked to the area, where they built houses, a general store, a restaurant, a pool hall, and a barbershop. At its peak, the town had more than 300 people living there.

The prosperity was short-lived. The semi-anthracite coal crumbled easily (friable), a high water table flooded the steeply sloping coal seams in the Bow River Valley, and the working space north of the railroad was limited. In 1904, Anthracite people gave up in favor of Bankhead, a much bigger mine.

Bankhead

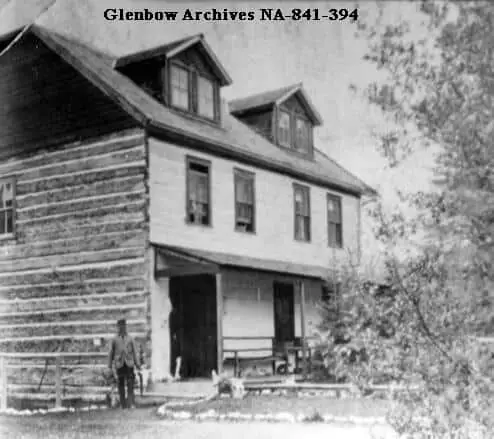

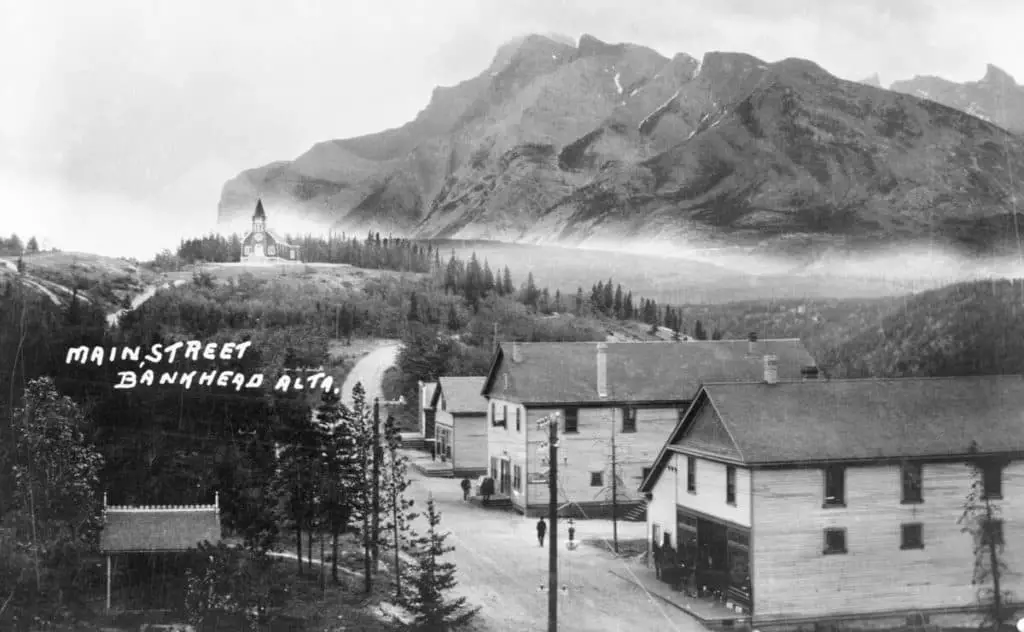

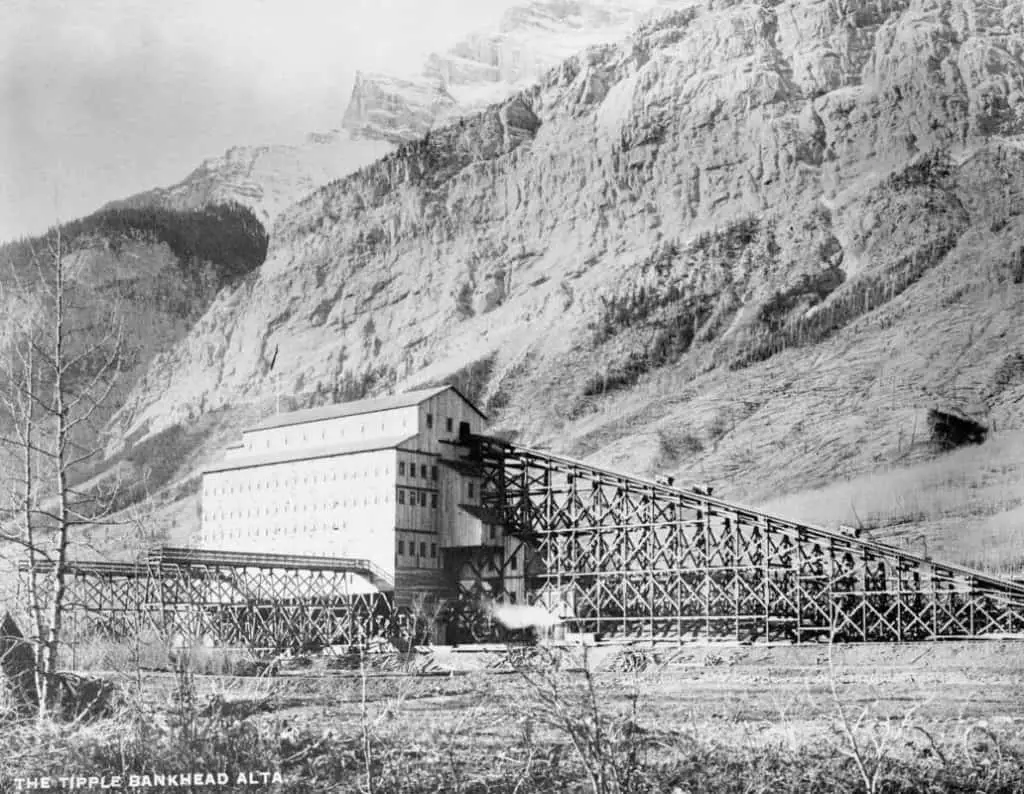

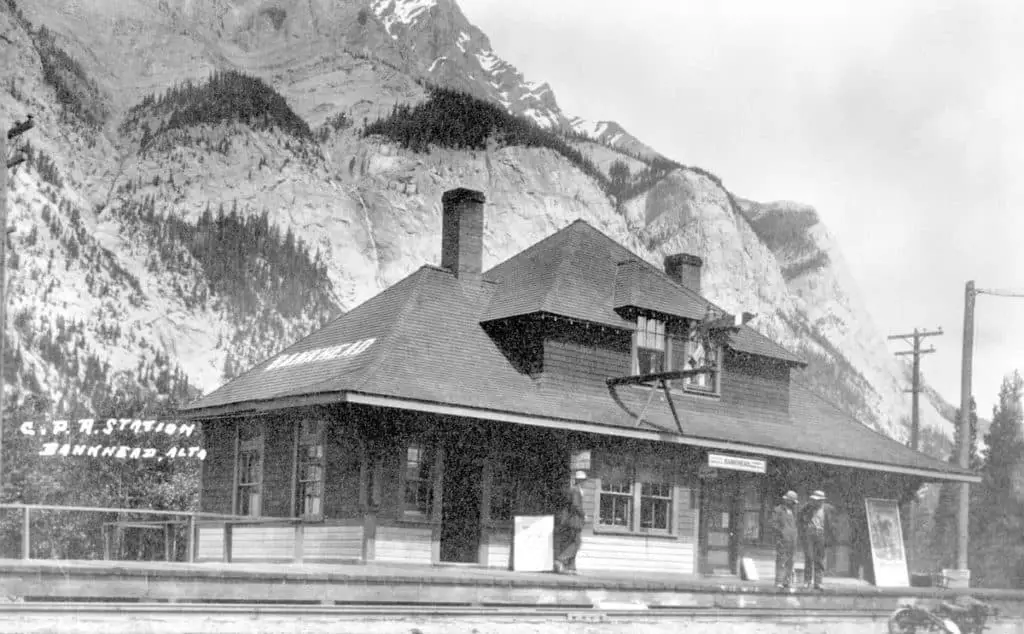

Bankhead was at the base of Cascade Mountain in Banff, two kilometers west of Anthracite and five kilometers east of Siding 29. It was established in 1903 on the upper terrace north of an anthracite coal mine operated by the Pacific Coal Company.

The company was a subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, which needed coal to power its locomotives. The coal mined at Bankhead was also used to power hotel boilers, like the one at the Banff Springs Hotel.

It had obtained an occupancy permit for 7,360 acres of coal land along the road to Devil’s Lake.

CPR had discovered 12 significant coal seams containing so-called semi-anthracite – because it was not as hard as the standard variety found in Anthracite – and built a railway spur to the mine.

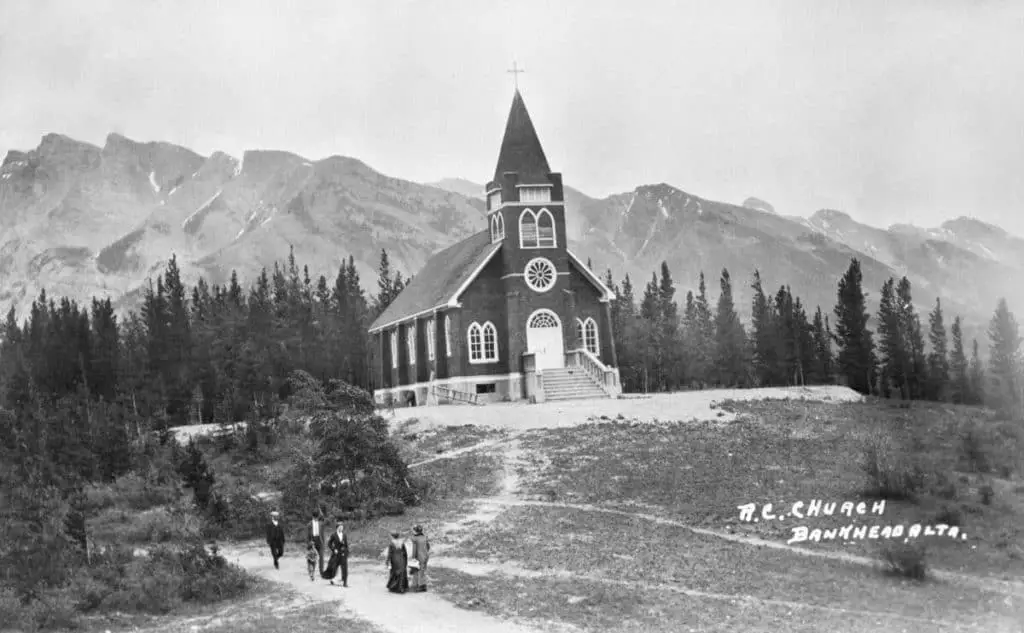

Bankhead, a company town, proliferated. It started with forty houses, offices, and a home for the mine’s supervisor, D.G. Wilson. Soon, the town also had a saloon, restaurant, hotel, shops, a butchery, a Roman Catholic church, a four-room school, and recreational amenities.

It expanded so swiftly that it began to rival the size of Banff. Bankhead even had water, electricity, and sewerage before Banff. In its heyday, it had over 100 residences and more than 1,000 residents.

Bankhead’s demise was triggered by disappointing (friable) coal and poor living conditions for the miners. The miners began a series of strikes, the latest lasted eight months.

They protested their dangerous working conditions (like exposure to toxic coal dust) and low pay. The mine closed on June 15, 1922, and Bankhead quickly became an abandoned ghost town.

Silver City

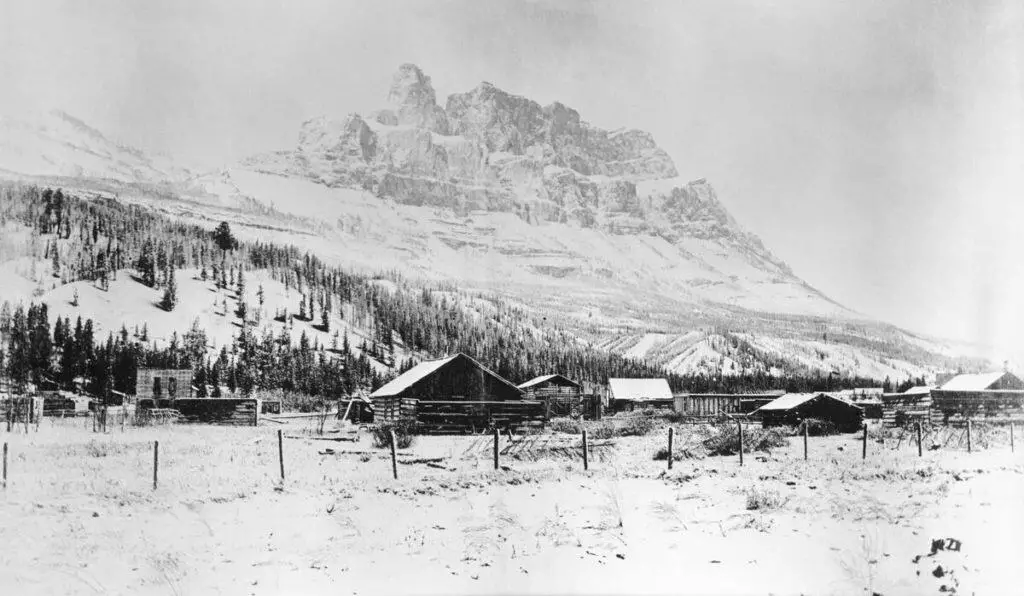

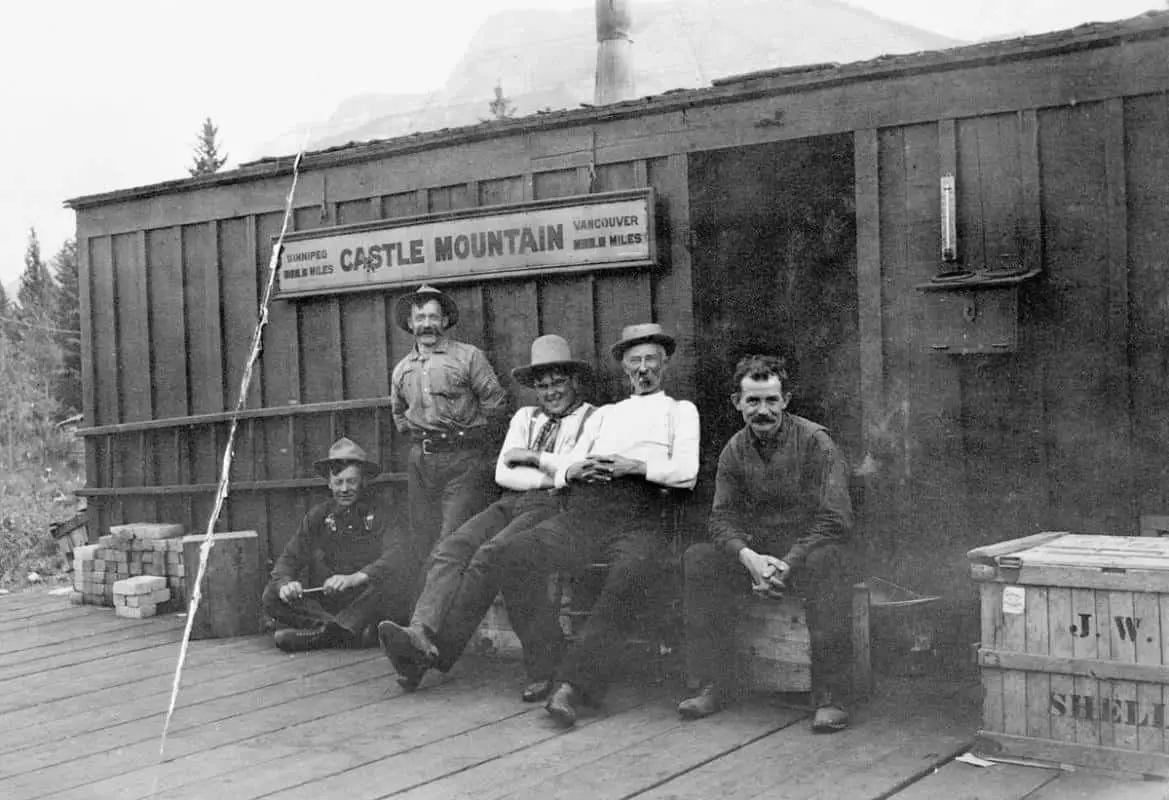

Silver City emerged in 1885 at the base of Castle Mountain, about halfway between Banff and Lake Louise.

The town’s origin started in 1881 when John Healy obtained a copper ore from a Stoney Nakoda man that was mined near Castle Mountain. He had the ore examined in Ford Benton, Montana, and it appeared fairly rich in silver. About one year later, he began prospecting in the Castle Mountain area.

At the time, CPR was constructing a railroad through the Rockies, and surveyors’ results indicated that the track would pass Castle Mountain. One year after the railroad was built, Healy returned to the area.

He and his brother Joe established a prospecting claim and gave it the name Copper Mine, though Silver City soon replaced it. Why this name was chosen remains a mystery, as no one ever mined silver in the area.

By then, a man named Joe Smith, who had worked on the railway through the Canadian Rockies, had relocated to Castle Mountain to go fur-trapping. When the railroad reached Silver City in November 1883, prospectors flocked to the region, hoping for a promising future.

The place boomed. In a matter of weeks, hotels, restaurants, stores, casinos, saloons, a train station, and houses were built. Others simply set up camp to find riches close to the town. Smith had his own pool hall and guesthouse, and business was good. At one point, Silver City was estimated to have a population of more than 3,000.

Two mines were developed: Alberta Mine on Copper Mountain on the other side of the Bow River and The Queen of the Slopes on the slopes of Castle Mountain. However, no precious metals were discovered. A survey of the area around Castle Mountain showed that there was iron ore, zinc, galena and copper but no precious metals. And Healy’s piece of ore later appeared to have nothing more than sulfides of lead.

Stories of fraud became increasingly prevalent, and the town developed much of a wild west atmosphere that hinged toward lawlessness. The North West Mounted Police was dispatched to establish law and order.

The euphoria, which had quickly swamped Silver City, subsided soon, and by the fall of 1884, the community had become a ghost town. Just a few people remained, and Joe Smith was one of them. He kept trapping in the area while hawking sold shoelaces, watches and buttons to passers-by.

During the First World War, registered aliens became his neighbors in an internment camp at Castle Mountain that the government had established. This camp contained a sizable number of Germans and Ukrainians.

Smith was to see Silver City temporarily revived when The Alaskan, a silent black and white adventure film, was filmed at Castle in 1924. To provide an authentic decor, the movie crew had the town partially rebuilt.

Smith had turned blind in 1937, and concerned friends had him moved to the Lacombe Home near Calgary, where he died soon after.

What Remnants Remain of the Banff Ghost Towns?

Ghost towns exuding the atmosphere of the wild west are appealing to many. So I can imagine you might wonder what remnants you can still find in the park that refer to the once-exciting days of yesteryear.

Sadly, the unsatisfying response is “barely anything.” Siding 29 transitioned into Banff, and the old houses and other buildings were all demolished or moved to Banff.

Remnants of the ghost town of Anthracite are almost entirely gone. The only thing left is the ruins of an old business building near Cascade Mountain (just south of the Trans-Canada Highway).

At the old location of Bankhead, you can still find the old railroad and some old coal cars, a locomotive, remains of Bankhead mine’s lamp house, the steps from Bankhead’s hilltop church, several foundations of buildings and huge slacks of coal at the mine site.

The old railroad station is the last authentic reminder of Bankhead. However, it is no longer visible at the former mining site. It was moved to Tunnel Mountain Road on the HI Hostel’s property, where you can still find it today.

Lower Bankhead is home to an interpretative walk that provides information on the town and its structures.

There are no remnants to be found at the Silver City location. All houses were demolished or moved from the area. A plaque in the grass close to Castle Mountain is the lone remnant of the former prospectors’ town.

The only ghost town still more or less intact is Minnewanka Landing. However, it’s challenging to get to because it is submerged in Lake Minnewanka. Underwater, you can find the ruins of the former resort town, including its houses, a bridge, and an old dam.

Location of Banff’s Ghost Towns

On the map below, you can find the location of the abovementioned ghost towns in Banff.

The only one worth visiting is Bankhead. It’s easy to find as it has a designated parking lot at Lake Minnewanka Road near Lower Bankhead.

Distances Table

Below you’ll find a distances table to the (former) ghost towns of Banff National Park. The distances are car kilometers, although you can only park your car close to Silver City and Bankhead.

The location of Anthracite is only accessible by bicycle along the Banff Legacy Trail because there are no nearby parking spaces for cars.

For Siding 29‘s location, park your car at the end of Hawk Avenue. However, there’s nothing to be seen there.

For Bankhead, you can park your car at the Lower Bankhead or Upper Bankhead parking lot.

For Silver City, you can park your car at the Bow Valley Parkway (Highway 1A) pull-out at the Castle Cliff Viewpoint.

Visiting Minnewanka Landing‘s location is, as said, quite challenging as the town is submerged in the lake. The only way to get there is to dive.

| DESTINATION | DISTANCE FROM BANFF | DISTANCE FROM LAKE LOUISE | TRAVEL TIME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anthracite | 7.3 km (4.53 mi) | 63.6 km (39.5 mi) | 8 min / 42 min |

| 2. Minnewanka Landing* | 13.8 m (8.57 mi) | 70.1 km (43.6 mi) | 18 min / 52 min |

| 3. Bankhead | 17.7 km (11 mi) | 72.4 km (45 mi) | 27 min / 60 min |

| 4. Siding 29 | 3.4 km (2.1 mi) | 58.1 km (36.1 mi) | 6 min / 37 min |

| 5. Silver City | 40.5 km (25.2 mi) | 28 km (17.4 mi) | 31 min / 20 min |

* You need to dive to this location as Minnewanka Landing is under water.

Photo attribution for the picture at the top of this post: Group at Castle Mountain railway station, Alberta, [ca. 1911], (CU178679).

Selected Sources

- Banff & Lake Louise History Explorer, Ernie Lakusta, Altitude Publishing Canada Ltd., 2004

- Banff: Canada’s First National Park, Eleanor G. Luxton, Summerthought, 2008

- Lake Louise Past to Present, Andrew Hampstead, Summerthought, 2016

- Camping in the Canadian Rockies, Walter Dwight Wilcox, Franklin Classics, 1896

- Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

- Town of Banff

I found your article very interesting. My grandfather John Sweeney born June 1884 in Mayo, Ireland died in Banff on August 27, 1911, but I have found no trace of him in any records. Do you know if there were Irishmen working in the mines in the early 1900’s? Thank you.

Hi Sharron,

Thanks for your message. Happy you enjoyed the article. I’m not sure about Anthracite, but I know Irishmen worked at the Bankhead mines.

Dan

This is excellent Dan! You may not be aware, but many Bankhead homes and the train station were moved to Banff and some remain. A group of us managed to save the station from demolition in the early 1980’s – and it can be seen at the Banff Youth Hostel on Tunnel Mountain. The Town of Banff has an excellent walking tour of heritage buildings, labeled by plaques.

Hi Doug,

I must admit I haven’t done the walking tour yet. But will do for sure. Thank you!

Dan