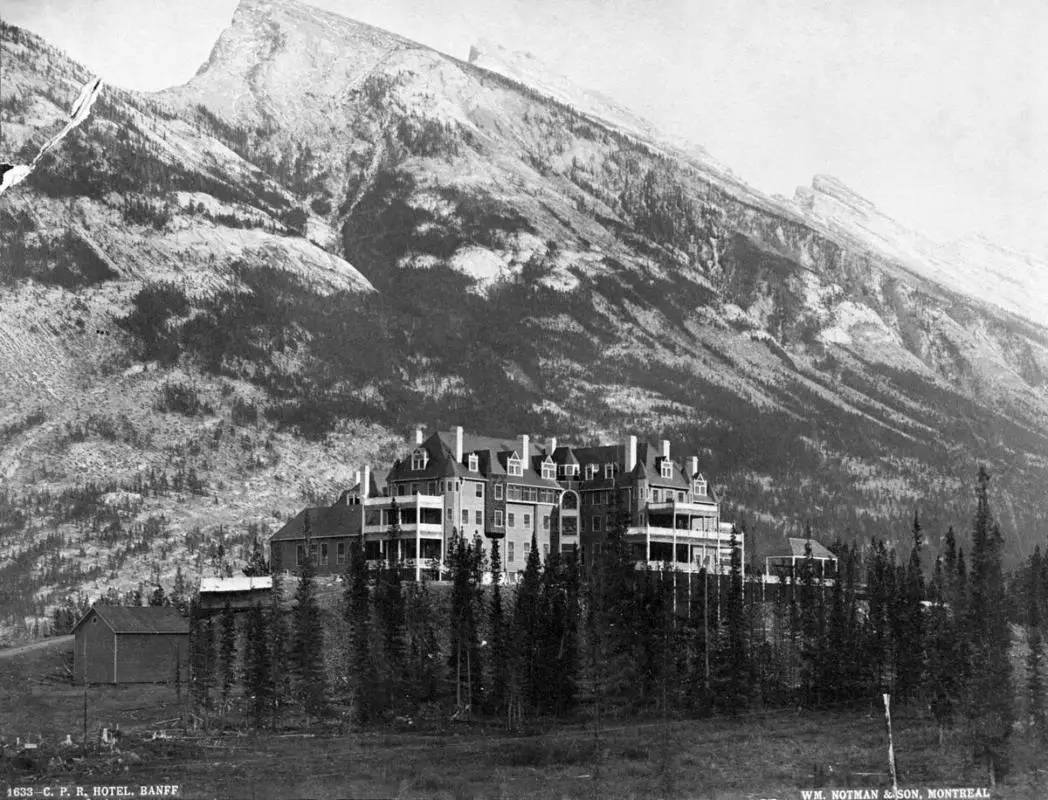

The Fascinating History of the Banff Springs Hotel

The Banff Springs Hotel is the most iconic building in Banff National Park. Even without staying there, it’s worth a visit. In this post, you’ll read about the hotel’s turbulent history.

I’ll never forget the moment I first saw the Banff Springs hotel emerging from the forest, the wild scent of pine trees piercing my nose.

It looked grand, majestic, impressive, and even daunting. Despite its size, it looked like it belonged there.

Set near the Spray River at the foot of Sulphur Mountain, this rock palace, affectionately called The Castle, is just a stone’s throw away from the birthplace of the park: The Sulphur Mountain hot springs.

The Banff Springs Hotel is enormous, impressive, and beautiful. And it possesses the grandeur you’d expect from a top resort hotel. Being well over a century old, it’s one of Alberta’s oldest buildings, and it has a fascinating history.

Let’s dive in.

Import Tourists to the Park

It’s probably the most famous quote about the area that became Banff National Park: “If we can’t export the scenery, we’ll have to import the tourists.

William Cornelis Van Horne, general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), uttered the sentence in 1883 after three of his railroad workers had discovered hot springs on a mountain slope in the Canadian Rocky Mountains.

The three laborers were part of the crew that built a railroad through the Rockies to connect British Columbia to the eastern provinces.

The CPR constructed facilities to feed and support the trains and their cargoes. In 1886, the CPR started building three “Railway Dining Stations” in British Columbia. They were Glacier House at Rogers Pass, Fraser Canyon Hotel at North Bend and Mount Stephen House at Field.

They were designed after Swiss chalets and had a central section with three stories and two wings pointing in opposite directions.

An amateur architect himself, Van Horne had his sights set on Siding 29 as he imagined a much larger hotel in the Canadian Rockies.

This new community – about three kilometers north of the present-day town of Banff – was located in a meadow at the foot of Cascade Mountain. It had a train station, two hotels, three shops, a horse stable, and a few flimsy buildings.

He realized that the spectacular mountain backdrop and the recently discovered hot springs had a lot of potential. It led to the creation of a 26-square-kilometer (10 sq mi) “Hot Springs Reservation”, officially designated by Order in Council 2197 in 1885.

Two years later, it had become the center of the newly established Rocky Mountain Park, a 670-kilometer (260 sq mi) public park.

Plans for a New Hotel

To transport guests from the train station to the hot springs, a road and a floating bridge were constructed in 1886. As tourists needed a place to stay, plans to build a hotel near the hot springs were developed that same year.

The location was different from the one Van Horne had imagined. He wanted to construct a hotel at the foot of Tunnel Mountain, on the north side of the Bow River.

When Tom Wilson, a CPR packer and guide, learned about it, he went to Van Horne and persuaded him that there was a much better location for the new hotel.

He led him to a location not far from the confluence of the Bow River and Spray River, which provided a view of the Bow Falls and the Bow Valley all the way to the Fairholme Mountains. Van Horne was impressed. He agreed that this was indeed a superior location.

The CPR manager soon contacted renowned architect Bruce Price to design the new hotel. Price was a well-known architect. He had earlier designed the CPR’s Windsor Station in Montreal.

His original sketch of the hotel contained 92 master rooms and 18 steward rooms, as Price wrote Van Horne in their correspondence.

During that time, one of the trends in North American architecture was “organicism“. This included the notion that a structure should be a natural, organic extension of its immediate surroundings.

Start of the Construction of the Banff Springs Hotel

In the fall of 1886, work on the hotel’s construction began. Railway workers, brought to Banff for the job, did most of the building. They were mostly Chinese.

By the early spring of 1888, the structure neared completion. It was a luxurious wooden structure, veneered to mimic cream-colored Winnipeg brick, with three stories, steep-hipped roofs, and pointed dormers.

The hotel’s interior was finished in local fir and pine. A glass-covered octagonal rotunda dominated the lobby. The higher levels had balconies in succeeding galleries that led to the central hall. That’s where the guest rooms were located; many were en suite.

A separate building housed a bathhouse with ten bathing rooms and a 9×24 meters plunge pool, fed by hot mineral water from the slopes of Sulphur Mountain.

The hotel was opened on 5 June 1888 and could accommodate 300 guests. George Holliday was appointed the hotel’s manager.

Van Horne was proud of what the hotel had become. He soon dubbed it the “finest hotel on the North American continent“. It appealed to the wealthy elites of Canadian society who first visited the hotel. They arrived by train and were taken to the hotel by a four- or six-horse-tally-ho. The ride took about twenty minutes.

They paid CAD 3.50 per night, twice as much as the other hotels in town charged.

In the hotel’s early days, Lady Agnes Macdonald, the wife of Canada’s first prime minister, was so enamored of Banff that she had her own cottage built adjacent to the hotel. She named it Earnscliff after the mansion she shared with her husband in the country’s capital of Ottawa.

Over the years, the hotel’s fame and reputation kept growing, drawing in more and more guests. By the early 1900s, some locals considered the hotel the “bread and butter” of the expanding town of Banff. At the time it had a few hundred residents.

Meanwhile, Van Horne had proven himself right. The Banff Springs meant a lucrative business for the CPR. At the turn of the century, it indeed ranked as one of the finest mountain resorts in North America.

The First Expansion of the Banff Springs Hotel

As a result of the hotel’s burgeoning fame and stature, a growing number of (international) clientele arrived, and soon it became clear that the hotel couldn’t handle the demand.

In 1900, the CPT planned the first hotel expansion and improvement. The west wing of the original structure was duplicated during a large expansion in the winter of 1902–1903. It was connected to the previous wing by a split-level passage.

It served as a southern extension of the wing it duplicated, giving the hotel its north-south orientation. Despite the considerable extension, it quickly turned out to be inadequate due to the hotel’s rising popularity.

The park’s superintendent noted in a 1903 report that no fewer than 5,000 visitors were turned away from Banff during the previous season. As a result, the hotel’s management developed plans for an additional extension.

The Second Expansion

This expansion started in 1904 and lasted until 1905. Although the exact nature of the addition is uncertain, it is possible that a six-story tower was constructed at that time on both the north and south wings. The new hotel could accommodate 450 people.

The following years saw several modest renovations, including a boiler, engine, washroom, and a significant renovation at the southeast corner, made of river rocks and a 90-foot smokestack.

Despite the hotel’s increased capacity, it kept dealing with a visitor overflow between 1907 and 1911. The demand was big. Over 400 tourists were escorted back to the train station in 1910 to spend the night in sleeping cars.

In 1911, the hotel unveiled a William Thomson-designed 9-hole golf course. A round of golf cost CAD 0.50, while a full day cost CAD 1.00.

Meanwhile, the hotel’s capacity issues clearly indicated its potential was not fully realized. The CPR management in Montreal concluded that “something new” needed to be constructed. Walter S. Painter, the CPR’s chief architect since 1905, was appointed to develop a new design.

Before he started working on it, he was taken on an “inspirational journey” of France’s Loire region and its medieval castles.

Construction of the Center Tower

After the summer of 1911, a crew of about 200 men started tearing out the old center portion. This was in preparation for the new concrete middle wing’s foundation. It was to become part of an 11-story center tower, 59.5 meters tall (195 ft). Two new swimming pools were also built.

The new building was an improvement over the previous one in many ways. In the early spring of 1912, the local newspaper Crag & Canyon reported a “general air of luxury” about the new hotel.

After the summer season was over, construction workers reassembled at the hotel to pick up where they left off. There were even more workers this time. Some estimates mention as many as 600 men.

They worked on what was to become “the tallest building in the Canadian Rockies”, and it had to be finished before the start of the 1914 season. Most people considered this impossible, despite Painter’s claims it wasn’t. But thirteen months later, the hotel manager announced that the “alterations” had been as good as completed.

The Painter Tower, which served as the hotel’s centerpiece, was 60 meters (197 feet) long, 21 meters (69 feet) wide, and 11 stories high. Its rock face was composed of Rundlestone quarried along the Spray River. No expense was spared. The CPR imported Scotch masons and Italian stone cutters to ensure the outside was of the highest caliber.

The tower had a dining area, a sizable dome that served as the lobby, and more than 300 guest rooms.

In May 1914, the renewed hotel opened.

One year later, the east wing of the old 1888 hotel, which had served as both the kitchen and the dining room, was torn down and replaced. In the same year, a new boiler and laundry room were constructed.

The hotel’s reputation and amenities were advancing in step. In 1924, the nine-hole golf course was expanded to include 18 holes. Soon after it began play, plans for an even greater golf course were already created.

Meanwhile, the plans drawn up in 1911 still hadn’t been completed. It took until 1925 before the CPR approved a new extension program. This involved destroying the old wooden wings to be replaced by rock-faced and fireproof structures.

The first wing was built in the winter of 1926-1927, the other the following winter. Adjacent to the south wing, a separate four-story annex with 100 rooms was built to accommodate guests while the wings were replaced.

A Fire in the Banff Springs Hotel

Then disaster struck. On 6 April 1926, the north wing of the annex caught fire; the addition had barely been finished. When Reginald Coysh, the hotel’s assistant manager, saw smoke pouring from the north wing at 11 a.m., he immediately ordered a fire report.

Within an hour, 500 (!) men were fighting the blaze. Many came from Calgary. Only two hours later, the fire had destroyed the entire wing.

Although made of stone, the central tower wasn’t spared from the fire. The north wing’s basement suffered an explosion that blew out many of the tower’s windows. The fire also destroyed the 13-year-old dining room.

The workers blasting at the north wing’s base during preconstruction were blamed for causing the blaze. They had started a fire not far from the old wing, and the flames spread to the structure.

Despite the setback, ambition surrounding the hotel prevailed, and the center tower’s restoration began right away. On 1 July, the hotel reopened its doors.

CPR engineer John W. Orrock designed the new wings. He created considerably larger north and south wings than Painter had intended. Also, he changed the roofline and increased the lower section of the center tower.

With work starting in September 1926, the north wing was replaced first. The south wing was added a year later, and the inner and outer swimming pools were rebuilt.

CPR president Sir Edward Beatty inaugurated the new hotel on 15 May 1928.

A New Golf Course for the Banff Springs

That same year, the newly constructed, more than CAD 500,000 golf course was unveiled. It had been designed by course architect Stanley Thompson and replaced the existing one.

At the time, the Banff Springs Golf Course was the most costly golf course ever built. The prairies provided topsoil for the fairways, British Columbia provided the bunker sand, and, not to forget, a special species of grass was brought in from the south.

The Devil’s Cauldron was the most challenging hole on the par-73 course. It was regarded as one of the toughest in North America.

During the course’s opening ceremony on 1 August 1928, Tom Wilson – who had persuaded then-CPR manager Van Horne in 1888 to have a look at the hotel’s current location – hit the opening shot.

In the subsequent decades, the Banff Springs would only see minor renovations. The hotel kept being a vibrant and busy location, continuously growing in popularity. But the effects of World War II put a stop to it.

The hotel’s European clientele stayed away, and the North American clientele substantially decreased. So much so that the hotel’s management was compelled to shut its doors in 1942 for the duration of the war.

A New Era for the Hotel

The post-World War II economic boom transformed travel. More and more people in North America owned cars; their popularity was unstoppable. With it came more and better roads, including more and better roads in Banff.

Commercial aviation took off as well. It changed the context of the hotel experience. As more and more middle-class travelers frequented the hotel, it ceased to be an exclusive bonanza that catered only to the rich and famous.

Over time, the number of middle-class guests at the hotel increased to the point where they became the “ruling class”, taking the place of the high society members that once called the Banff Springs their exclusive domain.

In 1962, the Trans-Canada Highway was completed, making Banff National Park even more accessible. Car owners could now access the park year-round. Or they just hopped on a bus to the park.

It created opportunities for the park’s ski slope owners. By the end of the 1960s, after primarily serving local skiers, it had grown into a popular ski resort, now also luring regional visitors.

As a result, the Banff Springs Hotel opened its doors for its first winter season on 5 December 1969. But things didn’t go as planned. In the early years, there weren’t enough visitors to cover the costs. A hotel teardown was considered.

The Arrival of Ivor Petrak

Things needed to change, and in 1971 this change was brought about by Ivor Petrak, the hotel’s new general manager, who was hired to manage the winter operation. He first turned down the job offer, then later accepted, looking for stability for his family.

This Czech-born hotelier had a background in international (European) hotel management and sound knowledge of the skiing business.

While drastically overhauling the hotel’s management and winterizing the hotel and its infrastructure, he also convinced the ski slope owners that a radical transformation was necessary to compete with the top ski resorts in the world.

His dominant approach to his work led to a comprehensive master plan for the hotel. It included a significant investment to revive the hotel. To cater to the winter market, he constructed new areas and bars.

Millions of dollars were spent on modernizing the hotel’s guest rooms, rewiring the hotel in 1975, and renovating the plumbing in 1978. Also, Petrak gave the arcade floor a second makeover so there would be room for shops and eateries.

In the fall of 1980, he launched yet another renovation of all the rooms and public areas and converted the outdoor pool into a hot pool.

Three years later, Petrak began a two-phase extension, in part to take advantage of the forthcoming 1988 Calgary Winter Games, including an expansion and update of the golf course.

Conversions and additions to the hotel were part of the initial phase. The Château Ramsay was connected to the upper and lower annexes. They were transformed into a guest wing with 246 rooms and a separate lobby and lounge. The Manor Highland Wing, the new addition to the hotel, was connected to the main building through an elevated walkway.

To the west of the hotel, across Spray Avenue, 336 staff apartments were constructed.

Petrak’s efforts over the past seventeen years had prepared the Banff Springs for a bright future. But by the time Winter Games had arrived in Calgary, it needed almost 100 million dollars for a significant update to keep its status, prestige and world-class amenities intact.

At the cost of $25 million, the Banff Springs Conference Centre was added. The facility, almost 3,200 square meters (34,000 square feet), opened in November 1990.

It became Canada’s largest conference center. It boasted a 252-seat theater, a conservatory, a ballroom that can hold 1,600 people, a business center, a grocery store, a bike rental shop, a car-rental company, a liquor store, and a bowling alley.

The Banff Springs now had 841 bedrooms and could accommodate 1,750 guests.

By the winter and summer of 1990, business was thriving. The hotel had become a symbol of tourism in Canada. That same year, Petrak resigned. Only three weeks after his farewell party, he passed away in 1991, aged 69.

A New Hotel Manager: Ted Kissane

The Banff Springs’ new general manager, Ted Kissane, began yet another renovation project. The guest rooms, the Manor Highland Wingand, the central kitchen, the entryway and the lobby were all renovated. And the golf course returned to its original Stanley Thompson layout (finished in 1999). Also, a first-rate spa was installed, which opened in 1995.

The prestigious facility called Solace Spa (now the Willow Stream Spa), measured 3,530 square meters (38,000 square foot), and included a Romanesque mineral pool.

Kissane also directed the Manor Highland Wing, which included small, less expensive rooms, to undergo another renovation and upgrade. They were doubled in size at the cost of 76 rooms, and upgraded to the same standard as the hotel’s more opulent suites.

Kissane’s creation of a new hotel lobby and entrance was another noticeable change to the hotel. The new space was about 2,200 square meters (23,680 square feet), almost double the size of the previous lobby.

The hotel branch of Canadian Pacific Railway, Canadian Pacific Hotels, was restructured as Fairmont Hotels and Resorts in 2001, taking the moniker from an American business it acquired in 1999. The hotel’s name was changed to Fairmont Banff Springs during re-branding.

The Ontario Municipal Workers Retirement System purchased Oxford Properties, a corporation that controlled seven Fairmont properties, including Banff Springs, in 2006.

Over time, the hotel’s room count decreased due to Kissane’s strategy to enlarge some rooms at the expense of others. His successor David Roberts continued to reduce the number of rooms, from 841 in 1988 to 764 in 2023.

It further cemented its reputation as a top-tier luxury resort hotel.

Just like Cornelius Van Horne had envisioned it in the late nineteenth century.

Wanna know about other historical figures in the history of Banff National Park? Read the post Banff’s Most Influential People: The Ones You Need to Know.

Banff Springs Hotel Facts & Figures

- Address: 405, Spray Avenue, Banff

- Opened: 1888

- Height: 59.5 m (195 ft)

- Floor count: 15

- Number of rooms: 764

- Number of restaurants/bars/eateries: 12

- Elevation: 1,414 meters (4,639 ft)

- Architects: Bruce Price, Walter S. Painter, John Orrock

- Owner: Oxford Properties

In case you’re interested, I also wrote a post about the history of Château Lake Louise. Check it out!

Want to book a room in the Banff Springs Hotel?

Check the latest rates on Booking.com

Selected Sources

- A Castle in the Wilderness: The Story of the Banff Springs Hotel, Bart Robinson, 2018, Summerthought Publishing

- The Fairmont Banff Springs Book, the Castle in the Rockies, France Ganon Pratte, 2013, Editions Continuite

- Historic Hotels Worldwide, website